____________________________________________________

"Padway feared a mob of religious enthusiasts more than anything on earth, no doubt because their mental processes were so utterly alien to his own."

____________________________________________________

"He reflected that there was this good in Christianity: By its concepts of the Millennium and Judgment Day it accustomed people to looking forward in a way that the older religions did not, and so prepared their minds for the conceptions of organic evolution and scientific progress."

____________________________________________________

L. Sprague De Camp's Lest Darkness Fall is often categorized as an alternate-history novel, and it sort of is one. I feel more compelled to call it a time-travel/alternate-history, because it seems to share more with a novel like A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court than it does with The Man in the High Castle, or Bring the Jubilee. That's because we don't see the consequences of a change in history throughout the action of the novel; rather, we see the changes themselves being instituted by a savvy, educated time traveler named Martin Padway.

Padway is a PhD student visiting Rome around the 1930s, when he is inexplicably transported to the sixth century A.D. (perhaps by a supernatural thunderstorm?) After gathering in his surroundings and accepting his new reality, Padway begins to focus on a concrete mission: preventing the advent of the Dark Ages. In other words, making sure that Darkness does not Fall. Padway goes about his mission in several remarkable ways, "inventing" the printing press and starting his own newspaper, revolutionizing contemporary systems of warfare, and introducing Arabic numerals to the Italo-Gothic world amongst many other things. The big concern turns out to be stopping the invading forces of the Byzantine Empire, and Padway takes a central role in making sure that the Byzantines do not win in this "branch" of historical time.

In his various political, economic, legal, and militaristic meddlings, Padway is certainly kept busy with some colorful characters and humorous situations. One pleasant surprise in this novel was the light, often funny tone that it often takes. It's certainly a ray of light in an otherwise dark genre --at least in this respect. It's also an easier, quicker read than most classic SF out there, as de Camp manages to convey the hectic pace of Padway's new life quite well.

I might even proffer the statement that de Camp's prose is too quick and cursory. Often, I felt I was reading a utilitarian, business-like summary of Padway's adventures in sixth-century Rome, instead of a rich novel. There were conversations and relationships that deserved more space to germinate --we'll often get an interesting exchange that seems cut short and we're onto the next segment before it seems like it the conversation had reached a fraction of its potential.

Nonetheless, this matter-of-fact style made it possible for de Camp to economically include plenty of information about the world of the sixth-century. This makes Lest Darkness Fall the kind of book that should awaken some enthusiasm for Roman history in the reader (it definitely did for me!). For this reason, I would recommend it to a high school class learning about ancient Rome --especially one that needs a break from dry, old textbooks.

All in all, Lest Darkness Fall was a good amount of fun, with a distinct 1930s tone to it that provoked a smile from this reader as often as its intentional attempts at humor did. As compared to more "serious classics" of the genre, like Bring the Jubilee and The Time Machine, this one probably isn't as profound or erudite, but it still managed to keep me interested and entertained (and I think entertainment value is where it beats out some of the established greats of the genre, rather than profundity). With its "young-adult fiction" style and the way it doesn't take itself too seriously, this novel is an appropriate choice for some light summer reading for SF and fantasy fans alike.

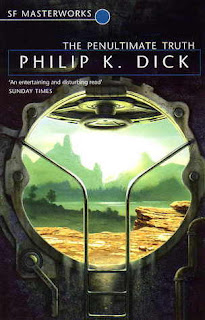

The Penultimate Truth:

_____________________________________________________

"Ye shall know the truth...and by this thou shalt enslave."

_____________________________________________________

"As a major component in his makeup...every world leader has had some fictional aspect. Especially during the last century. And of course in Roman times. What, for instance, was Nero really like? We don't know. They didn't know. And the same is true about Claudius. Was Claudius an idiot or a great, even saintly man? And the prophets, the religious..."

_____________________________________________________

" 'necessary'...A favorite word...of those driven by a yearning for power. The only necessity was an internal one, that of fulfilling their drives."

_____________________________________________________

Just when I thought Philip K. Dick had written a fairly straightforward, "traditional" SF story, he threw me another brilliant, convoluted, mind-bending curveball. Halfway through The Penultimate Truth, I was taken from the realm of Childhood's End and Dune, into a fractured story-scape with parallels to PKD's own Ubik and The Simulacra. In the interests of writing a spoiler-free review, I won't go into specifics too much here, but I will say that, after having read 10-12 PKD books thus far, there was a point in this novel where I put it down and said to myself, "Damn, Philip K. Dick, you've done it again."

The plot of The Penultimate Truth concerns itself with a near-future Earth, recovering from a nuclear war that ended thirteen years ago. Only no one ever told this fact to the hundreds of millions of people still hiding out in subterranean "ant-hills", who are led to believe that the war is still going on above their heads. An elite few live on the surface, feeding propaganda to the "tankers", all while reaping the fruits of the tankers' labors: robots that are supposedly manufactured for the war effort, in actuality, become personal servants for the ones aboveground. One tanker, Nicholas St. James, is forced, by dire circumstances within his ant-hill, to make a trip to the surface. His journey and subsequent discovery of the big lie make up just one small facet of the plot. We also get the perspectives of many above-grounders, including the most powerful handful, who are all jockeying for further power. We meet a propagandist, Joseph Adams, who seems to have some doubts about his job. And, as one might expect in a PKD novel, The Penultimate Truth touches upon themes of paranoia, depression, corruption, totalitarianism, anti-war sentiment, and falsehood. Really, the only thing missing is drugs!

Falsehood is especially central in this one. In Time Out of Joint, PKD explores the notion that someone's entire reality is a fabrication; a lie. Here, we get something very similar, on an even bigger level. In addition, PKD sprinkles in a lot of lying, misdirection and uncertainty throughout the plot...you'll start to feel like a tanker yourself, wondering just what the hell is going on.

As with most PKD novels, I feel inclined to point out a few specific touches that I especially enjoyed. While you can make legitimate complaints about the stylistic unevenness of his work, I don't think anyone can deny that PKD's brilliant imagination was impressive. Excellent scenes like the robot-committed murder of a sleeping man confirm this, in my view. This specific scene is grippingly suspenseful, and yet pitch-black humorous at the same time.

Another excellent touch comes in the form of Stanton Brose --the monstrous villain of the piece-- whose introduction makes him seem inhuman and mechanical, yet utterly repulsive (also see: Palmer Eldritch from PKD's Three Stigmata). David Lantano's programmed speech in Chapter 8 is yet another gem that I thoroughly enjoyed.

An admitted PKD-fanatic, I very much savored reading this enjoyably complex novel for the first time. The premise is one of PKD's stronger ones, although the writing seems a bit more rushed and sloppy than usual --with run-on sentences by the bunches providing an occasional annoyance. Easily read as an indictment of the class system, this novel is yet another one to add to the list of PKD works with anti-establishment undertones. It's also another novel to add to the list of his novels that are simply really good. To be frank, I'm not sure that I can say I've read a single novel of his that doesn't make that list.

No comments:

Post a Comment